On a window inside Tom Sachs’s New York studio, hand-stenciled letters spell out the words “This is not a pipe bomb.” Behind it, a pair of assistants labor over analog electronics. The Magritte joke sums up the wry glint of danger common to much of Sachs’s work; this is an artist who began his career fabricating functioning homemade guns as aesthetic objects. But it’s also a little unsettling, given that the whole place feels like a stray spark could send it up in flames.

Tom Sachs: Art and Soul

The artist revels in music, magic, and James Brown relics.

Interview by William HanleyPhotos by Tawni Bannister December 20, 2016

Sachs has occupied a warren of low-ceilinged spaces set behind a smeared storefront on the border of SoHo and Chinatown for more than two decades. Passageways snake between workstations, where assistants saw and solder, and shelves are jammed with Sachs’s materials of choice: spools of wire, cardboard, gaffer tape, boxes of white cigarette lighters. There’s an almost compulsive order to every tabletop or bin of screws. (This is unsurprising given that Sachs—a former assistant in Frank Gehry’s studio—coined the verb “to Knoll,” using the furniture maker’s name to describe carefully arranging objects at right angles.) Sachs has employed this hardware-store palette from his early work, such as a Chanel-branded chainsaw (1996) and guillotine (1998), to more recent endeavors, like a full-scale spacecraft made from plywood for his ongoing “Space Program” project, which peaked in 2012 with a thoroughly researched staging of a voyage to Mars inside New York’s Park Avenue Armory.

Whether Sachs is riffing on luxury brands or NASA, the tension between the real and the fake has fueled all of his projects. He has played out the representational drama of Magritte’s non-pipe in knockoffs, bootlegs, and homages that assert their own authenticity, more original in their shop-class imperfections than the commodities they approximate.

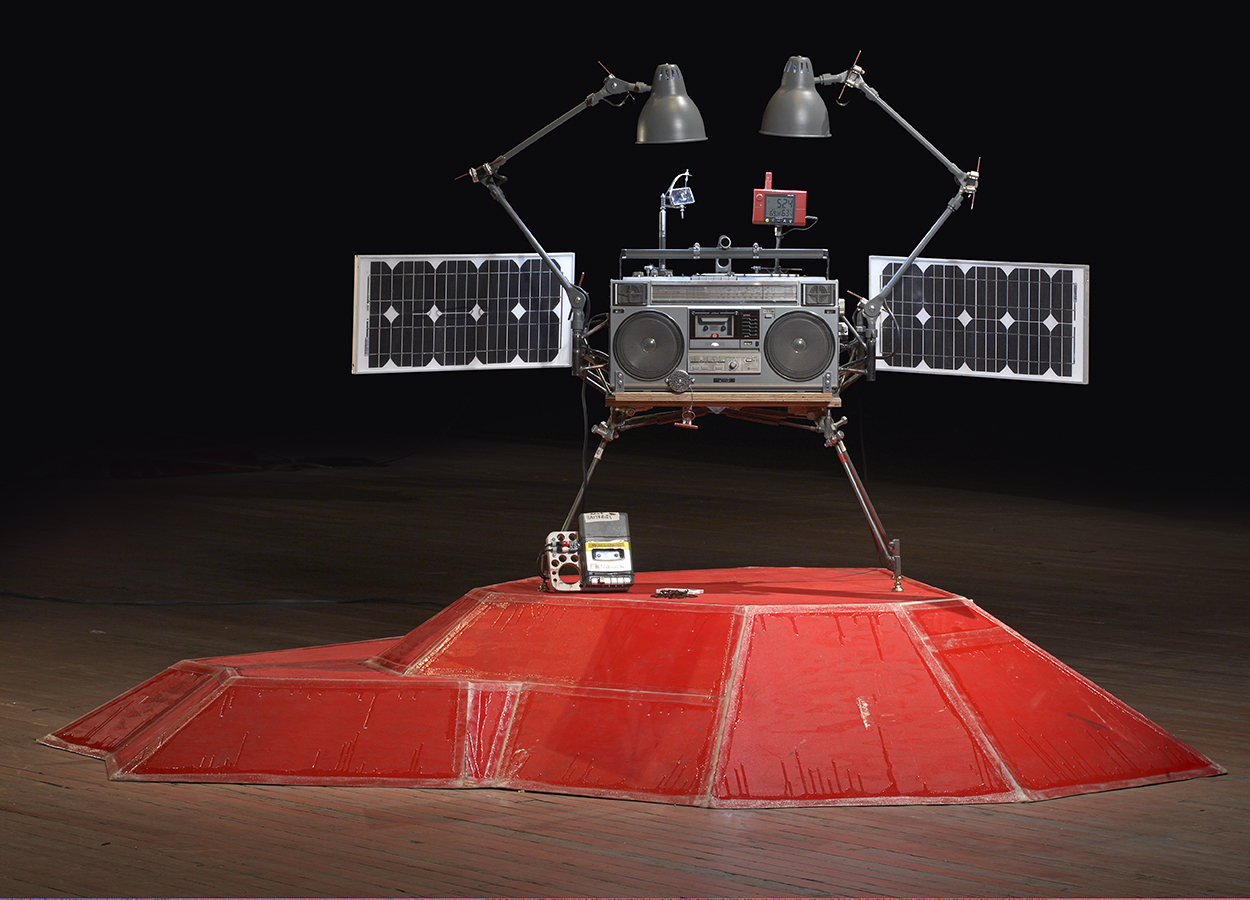

If this tension had a soundtrack, it would mix the insouciance of DIY punk with the brand-conscious swagger of hip-hop. Not coincidentally, music of all kinds has had a prominent place in Sachs’s work. Most directly, since the late ’90s, he has intermittently produced a series of boomboxes that cobble together vintage stereo equipment with elements of his larger projects to create totemic installations that double as working sound systems. A recent exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, titled “Boombox Retrospective,” gathered 18 of them. One, titled “Sarah” (2014), resembles a lunar lander topped by a katana; another, a modernist wall of speakers called “Toyan’s” (2002), was originally included in his project “Nutsy’s,” a room-sized installation that drew a line between Le Corbusier and McDonald’s using large foam-core models.

When Surface visited Sachs’s studio this fall, he had just returned from Japan, where his work is currently on view in a show at the Mori Art Museum (through Jan. 9, 2017). For all of the archness with which his work treats its source material, Sachs is earnest in his fascination with and affection for it. Sitting in Gehry-designed chairs in a sanctum-like space on one side of his studio, he spoke about everything from plywood and playlists to mortality and the godfather of soul.

I want to ask about the boomboxes, but first, I hear you’re somewhat obsessed with James Brown. Is that true?

Yes. People always ask me which artists inspire you, and I think they’re always expecting to hear Sol Lewitt, Chris Burden, Brancusi, or Marcel Duchamp. But I always say James Brown, Fela Kuti, Michael Jackson, and Bob Marley. These are the people who inspire me to make work as a sculptor. These are the people whose work moves me. George Clinton means 10 times what Yves Klein means—though I love Yves Klein—just in terms of what drives me.

Why place James Brown in that pantheon? You even made a series of works from his personal effects.

James Brown is the godfather of soul and the inventor of funk, disco, and hip hop. And he was a huge innovator in R&B. There’s no one who has invented more. He’s the Benjamin Franklin or Leonardo da Vinci of music. When he died, Christie’s did this disgusting auction, where they sold off what they could get their hands on, but they focused on his infamy. I thought it was a humiliating degradation of this man’s life. There were things like letters from prison that were not inspirational. For the James Brown works, I bought some of the objects, and I put them in reliquaries. I tried to elevate them, and treat them the way things like the Shroud of Turin are treated. I made “James Brown’s Last Supper” (2009)—literally his last meal in a vitrine—and I put his hair curlers in a cabinet in a mandala-like pattern [“James Brown’s Hair Products” (2009)]. I did his keys to the city [“Keys to Cities” (2008)], an homage to his passport [“Passport” (2011)], and a couple of other things. It was my way of trying to honor the greatness of James Brown, by focusing on his achievements.

You felt you were rescuing these objects from an insulting context?

They were presented in this auction in this embarrassing way. I wanted to present them as if they had belonged to the greatest man who had lived. The first black man to own his own jet. The first black man to own a radio station. The man who worked as a shoe-shine boy at a radio station and grew up to buy that radio station. This might sound tangential, but it’s important to have a little background. The most important artist of the 20th century is Louis Armstrong. He really represents the greatness and the tragedy of the diaspora. People were abducted from Africa, brought to the New World, forced to plow the fields and make cotton and tobacco so the country could gain economic independence from Europe. They would eventually be the foundation of an industrial powerhouse that could beat [Germany] in World War II, and eventually build rockets to go to the moon and kill God.

Kill God?

If you look at the space program as the greatest art project of all time, and going to another planet as the height of imperialism, as using science to eliminate religion, you see all of these horrible—all of these wonderful—things happened on the sweat of African bodies. When you think about the great artists of the 20th century—[Pablo] Picasso or Marcel Duchamp, or Walt Disney, or whoever—you’re missing the big picture. The arc goes Louis Armstrong, James Brown, Lil Wayne. James Brown is like the Mozart of our time.

Has everything you acquired been incorporated into works of your own, or are there objects that you have just to keep?

I’m not into stuff. I’m not a collector. My favorite things in the world pass through me. I’m just a maker. I always feel that when you make a sculpture or a painting or whatever, you should always feel like you never got enough money for it. It should always feel like it was a bad deal. You should love what you do so much that you don’t want to part with it under any conditions.

Even if you’re not a collector, much of your work involves artifacts, whether they’re pieces of James Brown memorabilia or byproducts of the “Space Program” project. Why has that always interested you?

It has to do with coming to terms with my mortality. I collected record albums when I was kid, and then I collected cassettes, and then CDs. Then I worked really hard on my iTunes library for years, and then just this last year, the assholes at Apple made all that work that I put into iTunes kind of disappear. I feel kind of defeated by it all. How many times have you gone through a dead person’s record collection?

I suppose very often.

Every time you go to a record store, you’re going through a dead person’s stuff. You have to remember that. When I die, all my shit’s going to get sold at Sotheby’s or Salvation Army, there’s no difference. The idea of building a perfect collection is an act of futility.

You seem to go deep in your process when creating works. What’s your mindset when you’re making?

Work can be a meditation. Part of the meditation is about clearing your mind, but you also cogitate and think about the issues and problems and questions in your life. Work for me is the more direct road to that. That’s my version of being in the zone. When I’m welding or cutting wood or drawing, the manual labor, all those hours add authenticity because you can say what you want about my sculpture, but you can’t take that away from me. It’s the time I put into it.

When did you start making boomboxes?

I think my first boombox was a Walkman velcroed to a piece of plywood with little battery-powered speakers and a handle that I made in wood shop with a place to hang headphones. Or when I installed a car stereo in my family’s station wagon. My sister’s boyfriend ripped off a really nice car stereo, and I traded a copy of Physical Graffiti for it. I hooked it up myself.

How did it become part of your artwork?

I made three for a gallery show because it seemed right. And then I made the giant one for “Nutsy’s.” After a while I realized that I had been making boomboxes and putting sound systems in sculptures for more than 20 years. It wasn’t something I planned. It naturally oozed its way into my work. Music is important to me, and the boombox, the iPhone, and the most expensive stereo, are all just music delivery systems.

What’s important is bringing music into our lives. An important part of the rituals in our lives is what’s playing. What was playing the first time you got or gave head? What was playing at your funeral?

I can only guess.

Think about the objects in our lives: the furniture we have, the clothes that we wear. They’re all expressions of who we are. If someone wears a Lil Wayne T-shirt, you’re going to be able to connect with them on that level, and if they’re wearing a Bon Jovi shirt, you’re going to connect with them on that level. When people dismiss consumerist stuff as taking you away from the spiritual, they’re right, but they’re also missing that it’s another form of communication.

Do you play music?

Not really. I’d like to. I tried doing percussion a lot, but I’m not so good at it. I’ve always had friends who are musicians. I don’t really like going to live concerts, though. They’re kind of boring. I have shit to make.

What do you listen to when you work?

You know I can’t listen to anything too good because I get distracted. So it’s either silence or sometimes Brian Eno or Bach. A lot of ambient music is like music for people who hate music. It’s kind of hard for me to find something I can listen to. Or I can listen to super-familiar stuff. Like old R&B that’s just like a texture I know well. You run into the problem there that you’re hearing the same song over and over again, and you’re not hearing it anymore. I don’t know. I prefer silence.

In the studio, it seems like everyone takes turns with their playlists.

Yeah, and I love that. I love the war that we have.

It’s a war?

Well—eeeh, not a war, but a battle. I can’t do some things. The Velvet Underground is like the Grateful Dead of punk. I’ve heard them too much. I always turn that off when someone puts it on. I like when we argue. It’s fun. We all learn something.

Do you have James Brown’s work ethic?

Obviously.

He was notoriously demanding of his band. Do you take a similar approach to your studio?

The video “Ten Bullets” (2012) is all about this. We have a [financial] penalty system here modeled on James Brown’s.

Has your band ever quit en masse?

It’s definitely a project, keeping it all together.

Tom Sachs’ James Brown Playlist

For our Dec./Jan. 2016 issue connecting art and music, Surface asked Tom Sachs to make us a mix of his favorite James Brown songs.